Wagner James Au: What made you decide to get so directly involved in Metaverse development?

Neal Stephenson: Interest in the Metaverse has been kind of slowly building for decades, and there have been various opportunities that have come my way from time to time to, you know, work for some company or other that’s trying to do something there. And I was kind of reluctant just because I didn’t want to throw my weight behind any one particular interpretation of it.

This happened also with the Diamond Age [his follow-up novel to Snow Crash], where I would hear from people who were wanting to make the young lady’s illustrated primer, and they all had totally different ideas. And most of the ideas seemed great, and I didn’t want to, like, officially endorse one or the other.

But things kind of came to a head last year, when suddenly, everything was Metaverse all day, all the time. And the idea that we’re working on with Lamina1 feels to me like it’s more foundational; it’s not one particular interpretation, or product, it’s kind of a base layer of functionality that anyone ought to be able to use to build experiences.

And so, as such, I sort of felt like I could get involved without kind of seeming to officially throw my weight behind this company or that company, this interpretation or that interpretation of what [the Metaverse] is supposed to be.

WJA: How exactly will Lamina1 work? Could you give me a specific example?

NS: What we’re trying to do is kind of lay down payment rails. In order to get from where we are now to the situation where the metaverse is a global communications medium, like TV or radio or whatever we have, to have experiences that people enjoy having. And by and large today, the people who know how to create those experiences work in the game industry. And some of them are happily employed, some are less happy; some are making good money, some are kind of struggling indie developers.

But the bottom line is that there needs to be a way for people who devoted their careers to acquiring skills with you know, Maya, or Blender or Unreal or Unity or any of the other tools that are part of the tool chain, a way for them to extract some some compensation if they are involved in making an experience that people enjoy and are willing to pay for it.

There are ways to do that with fiat currency, but it also seems to be a good match for the capabilities of cryptocurrency, which provides a way to send money back and forth between people, but also, as you know, additional functionality around smart contracts and so on, that can create what Jaron Lanier calls value chains, which is a way that a number of people could contribute to the creation of an experience and each derive some kind of compensation for their work. So that’s a somewhat abstract description.

WJA: The Unity Asset Store has quite a bit of that, at least in the sense that there’s a lot of game developers who sell their content on the Asset Store across multiple projects, and a lot of them are able to make a good living through fiat. So is this like the Unity Asset Store?

NS: The existing assets stores are, I think, kind of a valuable model for part of what we’re trying to do here. As you probably know, if you’ve looked at game engines and that stuff at all, just dragging and dropping an asset into a game is only the beginning of a pretty long process of actually making it function properly within the context of that game; typically you want to probably want to adjust the look of it, do some art, you may need to add animations, you certainly need to add some scripting, some sound effects. So the idea is to create a marketplace or payment rails where people who contribute to different aspects of something like that can get compensated for what they do.

WJA: So for example, one way that might work is, someone makes a cool car. And then someone else adds the physics to it and the interactivity, someone probably adds a heads-up display that can actually turn it into a game experience. And that’s all sold as one item but each of the people within that chain gets a cut. That fair?

NS: Yeah. We’ve been working with the team at Neon, a game studio here in Seattle that’s building Shrapnel, a AAA game on Unreal Engine that is going to be fully integrated with blockchain. And we’ve been working with some of their staff on ideas for how smart contracts might be structured in such a way as to facilitate these kinds of value chains.

WJA: So this is an interesting place we’re at now, because the founders of many existing metaverse platforms, including Fortnite Creative, Roblox, Oculus/Meta, and Second Life were directly inspired by Snow Crash. Are there plans in place to have Lamina1 directly work with them?

NS: No. I mean, never say never, but the kinds of companies that you mentioned are operating big platforms that are well established, with a customer base and a presence in the marketing world and are beholden to their existing customer base and shareholders. We intend to build what we want to build. It’s intended as an open platform, and so anybody who wants to can, should be able to link into it, and use it if it’s useful to them. But we don’t have any direct plans or intentions about partnering with companies that you mentioned.

WJA: When I define the Metaverse I adhere as closely as possible to what you described in Snow Crash because like I said, so many companies have been directly inspired by it. But I’ve been curious, 30 years later, what’s your own working definition?

NS: In a weird way I don’t need one, since I’m the one who coined the term. I would say the basic idea behind the Metaverse from 30 years ago is still applicable and is basically: What would it take content-wise to make 3D immersive graphics into as broadly popular as television?

And so my main concern at the time I wrote the book was that the hardware [back then] was incredibly expensive, and still slow. But you can easily imagine that changing in the future. So that’s always the way it works with hardware; over time, it gets radically faster and cheaper.

And so that has happened. It’s happened largely because of the game industry.

You know, Doom came out the year after Snow Crash was published, The World Wide Web was launched basically the same year. And so those kinds of developments created a big consumer demand for computers that can show graphics, first two dimensional and then three dimensional graphics. So that part of it has happened. Almost everyone now has got some kind of a device that can render at least simple three dimensional scenery.

And so the next step is, creating the kinds of experiences that are going to draw people in. And I still stick with the basic conceit, I guess you could say, of the Metaverse and Snow Crash, which is that they should be linked in a kind of spatial arrangement.

What’s lacking in the World Wide Web [is], you’ve got this web of hyperlinks all over the place that jump you from one site to another and there’s not really a kind of spatial organization that ties it all together. I think there should be a spatial way of tying it all together.

So I think that’s another kind of fundamental aspect of the Metaverse. And stuff that’s almost too obvious to mention, but you know, multi-user on a massive scale; interoperability is kind of implied and kind of necessary, and just certain constraints as to the scaling and physics. So, you know, gravity is pointed down, avatars are all kind of the same size, so that the thing just kind of makes sense and hangs together as a three dimensional construct.

WJA: You mentioned at one point in Snow Crash that the Metaverse has a concurrency twice the population of New York. So I checked the population in 1992 when you wrote it, and that’s about 15 million. And that’s actually what the population or the peak concurrency of Roblox, Fortnight, and so on is — there are about 15 million people in these platforms at any given time.

NS: That’s an interesting stat. Cool idea.

WJA: Here’s I guess a devil’s advocate question: The blockchain hasn’t really worked for any other metaverse platform, and there’s been several. The key factor, far as I can tell, is creating value to virtual land, as the first and foremost principle, leads to just rabid real estate speculation, but not really community. And so there’s not this flywheel of user-created content that we’ve seen in Second Life and other platforms.

So how do you think Lamina1 one will succeed as a blockchain-facing tech? No technology where others have not?

NS: Why are dollars valuable? Because you can buy regular stuff with them, stuff that you actually need in the real economy. People do speculate in dollars, there are currency speculators, but it’s a small fraction of the number of people who engage in dollar transactions every day. And you can make similar comments about real estate in the real world. But why is it valuable?

Well, it’s valuable, because hopefully, people are using it to do interesting things. Again, there are people who speculate in real estate, who buy property because they think that the value is going to go up.

But at the end of the day, the value is grounded in something — a real economic value that is happening on different patches of land. So I think that the same is true of virtual real estate and cryptocurrency, is that the value is going to arise from — in the case of real estate — from the use of that real estate to, as you say, build communities and create experiences that people enjoy having.

And if people enjoy having those experiences, then that suggests to me that they’ll pay for the privilege. And so now you’ve got a real economy that’s using tokens to pay for virtual goods and services and compensate the people who made those.

And it doesn’t prevent speculation, you can never prevent people from engaging in speculative activity, but [Lamina1] is not a company that is going to fund itself by putting out an ICO or something like that. We’re seeking investment through normal tech investor channels. And you know, when it comes time to establish a market for real estate, we want that to be based on, again, on something more than just pure speculation.

That’s why we’re focusing, like I said, on creating tools and kind of foundational utilities that content builders are going to need. Because if they don’t show up and begin to populate the Metaverse with interesting experiences, then there’s no there there. And the only thing that’s left is speculation.

WJA: What’s the status of the Snow Crash adaptation as a series on HBO?

NS: HBO Max was developing it for television, until I think it was something like April or May 2021. And then they passed on it. So it all reverted back to Paramount, and I think it’s still up in the air — is it a TV series? Is it a limited series or an ongoing series? Is it a movie or a series of movies? So you’d have to touch base with them to try to get the latest on that front.

WJA: It’s sort of in this paradoxical place where because it’s so extremely influential, turning it into a movie might seem derivative, because there’s been so many things based on the Snow Crash.

NS: It’s been interesting to watch over the years. You know, when we started talking about film adaptation in the 90s, obviously, you think about the state of computer graphics in 1995.

And then imagine making that movie with those graphics. Maybe you make it a little nicer because you’re looking into the future but you know, today if we were to watch a 1995 adaptation of Snow Crash, we would be immediately pulled out of the story by the obviously substandard graphics from 27 years ago.

And so, over time, now, we’ve kind of reached the point where it’s not clear that you would even use computer graphics. I mean, you could film actors playing whatever role and just claim that they were photorealistic avatars.

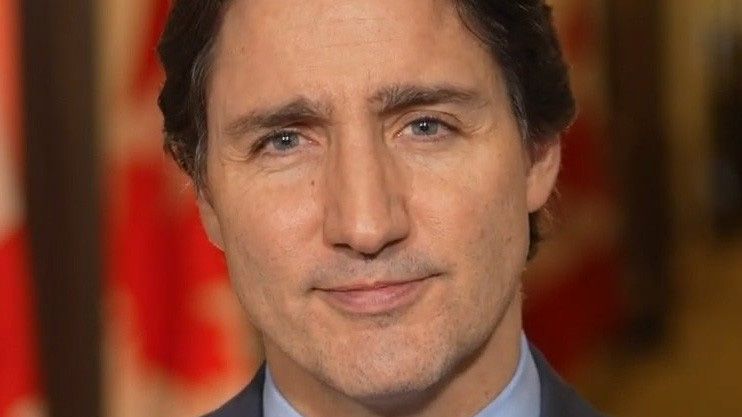

Stephenson image copyright Lamina1

Read More: nwn.blogs.com

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  XRP

XRP  Tether

Tether  Solana

Solana  Dogecoin

Dogecoin  USDC

USDC  Cardano

Cardano  Lido Staked Ether

Lido Staked Ether  TRON

TRON  Avalanche

Avalanche  Wrapped stETH

Wrapped stETH  Sui

Sui  Chainlink

Chainlink  Toncoin

Toncoin  Shiba Inu

Shiba Inu  Stellar

Stellar  Wrapped Bitcoin

Wrapped Bitcoin  Polkadot

Polkadot  Hedera

Hedera  WETH

WETH  Bitcoin Cash

Bitcoin Cash  Uniswap

Uniswap  Pepe

Pepe  Litecoin

Litecoin  Hyperliquid

Hyperliquid  LEO Token

LEO Token  Wrapped eETH

Wrapped eETH  NEAR Protocol

NEAR Protocol  Internet Computer

Internet Computer  Ethena USDe

Ethena USDe  USDS

USDS  Aptos

Aptos  Aave

Aave  Render

Render  Mantle

Mantle  Bittensor

Bittensor  POL (ex-MATIC)

POL (ex-MATIC)  Cronos

Cronos  Ethereum Classic

Ethereum Classic  Artificial Superintelligence Alliance

Artificial Superintelligence Alliance  MANTRA

MANTRA  WhiteBIT Coin

WhiteBIT Coin  Arbitrum

Arbitrum  Virtuals Protocol

Virtuals Protocol  Monero

Monero  Tokenize Xchange

Tokenize Xchange