[ad_1]

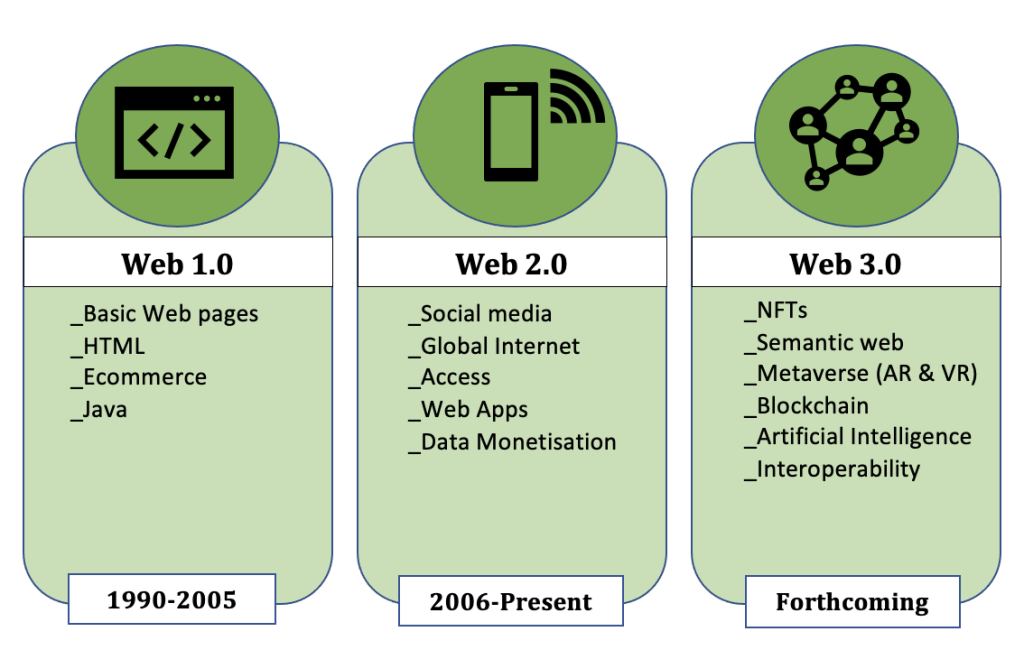

The streets of Brasilia, Brazil’s capital, erupted in celebration at the inauguration of the nation’s new president on 1 January 2023. Chants of “Ole, ole, ola, Lula, Lula!” welcomed the new head of state, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has pledged to restore protections for the country’s Amazon rainforest. Just weeks into his term, that promise is already being tested, as the emergence of fresh carbon market schemes in the Amazon brings with it a new and poorly understood opportunity and threat: Web3.

In theory, Web3 is exciting for climate action – it is an internet not controlled by a select few but is instead decentralised and powered by blockchain technology that promises the transparency decarbonisation has notoriously lacked. At the forefront of this new era is regenerative finance, nicknamed ‘ReFi’ in Web3 communities, a new economic approach that combines the paradigm of Web3 technology with the urgent need for climate action.

Web3 and blockchain technology can enhance transparency and efficiency in voluntary carbon markets, where companies and individuals can purchase carbon credits to offset their carbon emissions. These markets are typically less regulated than mandatory carbon markets and are used to achieve corporate sustainability goals or to offset emissions that are not covered by compulsory schemes.

Web3 and blockchain can create a decentralised and tamper-proof platform for carbon market credit tracking and verification. ReFi can be integrated by allowing for the creation of carbon credit-based financial instruments, enabling companies and individuals to trade carbon credits as assets and use them as collateral for loans, creating new opportunities for carbon credit financing and investment.

The idea of a global carbon market is still nascent, however. It was only months ago at COP27 that experts voiced concerns over the ability of the regulatory framework envisaged under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement to account for issues like indigenous rights, double counting and, fundamentally, the lack of a definition for what constitutes a carbon sink. The emergence of Web3 carbon offset projects in the absence of clearer, stronger carbon market regulation could spell meta-scale trouble, warn experts.

“Many crypto credits are little more than a fancy repackaging of existing carbon credits,” says Khaled Diab, communications director at the NGO Carbon Market Watch. “If they are reselling a credit that has already been sold before, [there are] no new climate benefits, only revenue for the seller.”

President Lula’s government has acted swiftly to block Nemus, one project demonstrating the dangers of jumping the regulatory gun. The company attempted to buy more than 150 square miles of Amazon rainforest and sold non-fungible tokens (NFTs) corresponding to plots of land to buyers called “guardians”. While the guardians did not technically own the land, they did have a say in the types of projects undertaken on the territory.

However, members of indigenous groups in the area raised concerns that the land is already spoken for and that Nemus had not consulted the people living there. Additionally, the company did not actually secure ownership of the land in question, despite selling more than 1,500 NFTs.

In response to these concerns, federal prosecutors in the state of Amazonas have recommended that Nemus immediately stop commercialising NFTs on indigenous territory and refrain from contacting or co-opting indigenous leaders without following the requirements of the International Labour Organization, such as the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (1989) and various frameworks on workers’ rights and gender equality and non-discrimination. The recommendation comes after decades of exploitation and disruption of the region by companies seeking to profit from its natural resources and follows efforts by the Apurina indigenous group to restore harmony to their community.

Tokenising carbon

Not long ago, cryptocurrency was notorious for its exorbitant energy intensity. Thanks to its mining modus operandum, proof-of-work (PoW), crypto racked up a carbon debt higher than many of the world’s countries combined. However, in September 2022, Ethereum, the second-largest cryptocurrency platform after Bitcoin, significantly reduced its power consumption through an event known as the Merge. By switching the blockchain’s PoW mining system to an alternative called proof-of-stake (PoS), Ethereum decreased its electricity consumption by 99.84% – a reduction equivalent to the yearly power needs of Ireland or Austria.

“Because the vast majority of hit NFT projects were built on Ethereum, pre-Merge, we could argue that those transactions were not climate-friendly, but we can’t really say that anymore,” says Nihar Neelakanti, CEO of Ecosapiens, a company specialising in carbon capture NFTs. “A single NFT transaction on [post-Merge] Ethereum uses less energy than watching one TikTok video. PoS networks like Ethereum use less energy than Web2 internet services like Netflix and YouTube. I think this will likely help NFTs go more mainstream. More creators and buyers that were on the fence because of the carbon footprint will jump on board.”

“NFTs are more than just JPEGs,” continues Neelakanti. “The underlying smart contract is a really exciting piece of technology that can enable more commodities and assets to swap hands easily, like real estate deeds, for example. [They] can be leveraged to raise awareness and capital for social good in an incredibly swift and easy way that traditional philanthropy and ESG bonds can’t.”

NFTs enable a new type of fundraising mechanism and impact investing, through which individuals can purchase unique NFTs that support a social cause or represent a share in a social impact project. Additionally, NFTs make tokenised donation possible, whereby individuals can make donations to charity using cryptocurrency, which can increase the transparency of a donation and its impact.

Neelakanti says Ecosapiens offers the world’s first carbon-backed digital collectables. Each NFT offsets 15 tonnes of carbon – via reforestation carbon credits – or [an average American’s] full year’s worth of carbon emissions. Ecosapiens sources its carbon credits from third-party carbon brokerages Cloverly and Patch, whose carbon credits are verified by independent carbon registries such as Puro.earth.

Carbon Market Watch’s Diab is wary, albeit not untrusting, of companies like Ecosapiens. “Sourcing from a third party is not a problem if it comes directly from a credible standard and is sold only once,” he says. “However, if they sell it for a gigantic markup, as has occurred before with NFTs, then that money is going to the seller and not to finance climate action or benefit local communities.”

Some people may choose to buy carbon offset NFTs instead of purchasing carbon offsets directly because NFTs are a more tangible and visible way to demonstrate their commitment to reducing their carbon footprint. Additionally, NFTs can be bought and sold on blockchain marketplaces, which allows for a transparent and verifiable way to track the ownership and impact of carbon offset projects. Carbon offset NFTs also provide a unique selling point for collectors and investors looking to buy into the ESG trend, which has sparked criticism in some areas for creating a large markup on carbon credits and tainting the values on which carbon markets are built.

One such case made headlines in January 2021, when UK-based cryptocurrency venture Save Planet Earth sold a carbon credit representing a tonne (t) of CO2 as an NFT for $70,000 at auction. Credits from the same project were trading for less than $20 from voluntary carbon offset providers at the time and the average price of a forest carbon offset was just $4.73/t.

Web3: the carbon market hustle

“For a public launch of 10,000 NFTs, Ecosapiens would collectively offset 150,000t of emissions, which is the largest purchase of carbon in Web3, and equivalent to that of the largest F500 carbon buyers like Microsoft and Stripe,” says Neelakanti. “When a user buys an Ecosapien collectable, the capital goes towards carbon credits that sequester new carbon, linking them back to the collectable. For the consumer, however, it just feels as easy as one click.”

A polished user experience may add a veneer of simplicity, but the intricacies of carbon credit generation and trading remain beneath the surface. Diab cautions that companies should avoid offering tonne-for-tonne offsets, such as using one tonne of carbon sequestered by trees to offset one tonne of fossil fuels burned. “It is deceptive or at least misleading and gives buyers the idea that they can neutralise their climate impact by buying these credits – which is far from reality,” he says.

“Estimating the actual number of tonnes of [emissions] reductions is nowhere near an exact science,” he explains.

There is also the issue of permanence when using trees for offsets. Without a guarantee to safeguard forests used as offsets, and compensation for their destruction from increasingly common droughts and fires, they cannot credibly equal fossil fuels burned, which “have been in the ground for millions of years”, as Diab puts it.

[Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter]

He raises the issue of double counting too. “If a state has already counted this reforestation as part of its national inventory, a private actor then claiming it is highly problematic,” he says. Companies should offer buyers the option to buy contributions to climate action instead, he suggests.

Rarible, crowned one of the leading NFT marketplaces for 2023 by Forbes, offers buyers the option to offset the energy consumption of their purchases at checkout via Nori, a third-party carbon broker. Yet, when Energy Monitor asked Alex Salnikov, Rarible’s co-founder, for examples of innovative carbon removal or environmental NFTs available in the marketplace, he could not give any. “It is nearly impossible for us to keep track of every NFT that is minted on our marketplace,” Salnikov said. “There are many projects in the space that are geared towards sustainability.”

ReFi projects could benefit the race to net zero, but without a robust regulatory framework to ensure transparency and compliance with a set of laws governing carbon markets, unscrupulous vendors could take advantage of consumers and climate change would lose out.

[ad_2]

Read More: news.google.com

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  Tether

Tether  XRP

XRP  Solana

Solana  USDC

USDC  TRON

TRON  Dogecoin

Dogecoin  Lido Staked Ether

Lido Staked Ether  Cardano

Cardano  Wrapped Bitcoin

Wrapped Bitcoin  Hyperliquid

Hyperliquid  Wrapped stETH

Wrapped stETH  Sui

Sui  Bitcoin Cash

Bitcoin Cash  Chainlink

Chainlink  LEO Token

LEO Token  Stellar

Stellar  Avalanche

Avalanche  USDS

USDS  Toncoin

Toncoin  WhiteBIT Coin

WhiteBIT Coin  Shiba Inu

Shiba Inu  WETH

WETH  Litecoin

Litecoin  Hedera

Hedera  Wrapped eETH

Wrapped eETH  Binance Bridged USDT (BNB Smart Chain)

Binance Bridged USDT (BNB Smart Chain)  Monero

Monero  Ethena USDe

Ethena USDe  Polkadot

Polkadot  Bitget Token

Bitget Token  Coinbase Wrapped BTC

Coinbase Wrapped BTC  Pepe

Pepe  Uniswap

Uniswap  Pi Network

Pi Network  Aave

Aave  Dai

Dai  Ethena Staked USDe

Ethena Staked USDe  Bittensor

Bittensor  OKB

OKB  BlackRock USD Institutional Digital Liquidity Fund

BlackRock USD Institutional Digital Liquidity Fund  Aptos

Aptos  NEAR Protocol

NEAR Protocol  sUSDS

sUSDS  Internet Computer

Internet Computer  Cronos

Cronos  Jito Staked SOL

Jito Staked SOL  Ethereum Classic

Ethereum Classic