Two years ago, an explosion in Alexandra Assouad’s hometown of Beirut, Lebanon killed 218 people, leaving Assouad emotionally devastated. She complained of tension in her arms and neck, but later realized she was suffering somatic symptoms from the stressful explosion.

Assouad, who was living in Toronto at the time, partnered with three other immigrant women in the area who shared Assouad’s interest in mental health issues. Together, they launched a mental health platform with an emphasis on cultural sensitivity and understanding the mental health needs of communities that are underrepresented in mental health research.

Their company, Mind-Easy, started with a mobile platform that provides mental health check-ins using AI-based avatars that help users unpack their feelings, engage with their emotions and access relevant educational resources about stress, depression and other topics.

“We’re able to pick up on qualitative and quantitative data and somatic symptoms,” Assouad said.

With these different inputs, Mind-Easy’s module can redirect users to the company’s content.

Mind-Easy’s avatars are created with videos, not illustrations. The 30 ethnic avatars speak more than 100 languages, dialects and accents. Assouad said the company found that some users, particularly people of color, feel more comfortable sharing their secrets and insecurities with a bot that won’t judge them or project their own cultural values.

Entering the Metaverse

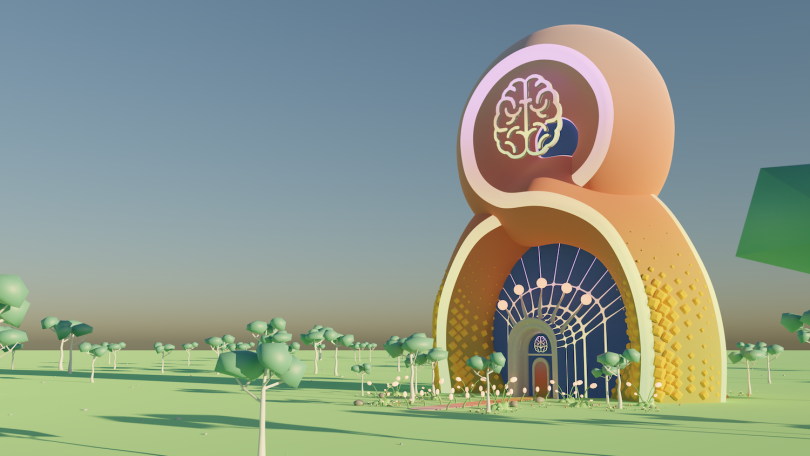

Mind-Easy recently expanded its mental health resources beyond its mobile app and into the metaverse.

On World Mental Health Day, Toronto-based Mind-Easy opened the first mental health clinic on Decentraland, a decentralized metaverse where users can buy land using an Ethereum-based currency called MANA.

Mind-Easy received grant funding to build a mental health clinic from the Decentraland community through its Decentralized Autonomous Organization [DAO], an organizational structure that allows users to vote on matters of importance to the community.

On Decentraland, Mind-Easy hosts a library of more than 50 educational videos that might be of particular interest to metaverse users — issues like avoidance, gambling addiction and perception of one’s identity.

When entering the Mind-Easy mental health clinic in the metaverse, an AI bot asks users questions about their mental health. Depending on the users’ answers, the walls will change color and the music will change to create a desired atmosphere.

“Your moods and emotions are being reflected in your environment, and then it dynamically calms you down as you do the check-in,” said Akanksha Shelat, Mind-Easy’s CTO.

The building also guides the user in breathing exercises. The user is encouraged to inhale when the building’s walls contract and exhale when the walls expand.

An Emerging Market

Metaverse environments give their denizens a chance to create a digital utopia, so it only makes sense that mental health clinics are cropping up in this new virtual frontier.

Mind-Easy is one of several mental health startups experimenting with the healing potential of avatars, virtual reality and the metaverse.

In London, mental health company Emplomind has also built a mental health clinic in Decentraland and is in the final stages of planning a launch event.

Los Angeles startup TRIPP guides virtual reality meditation sessions with immersive visual and audio experiences that mimic a psychedelic trip.

Because the metaverse is relatively new, it’s yet to be seen what effect these experiments will have on mental health outcomes. While there are some concerns about users, especially children, immersing themselves in an alternate reality, the metaverse also has the potential to reduce loneliness and expand access to mental health care to those who may not have sought it out otherwise.

Assouad said she shares concerns about metaverse users disassociating and losing touch with reality — a topic Mind-Easy is researching with its metaverse clinic — but she also sees an opportunity to provide mental health resources that are more culturally sensitive for people of color.

“We wanted to make sure that cultural competence was one of the minimum standards when it came to the intersection of mental health and the metaverse, just because we’ve seen that wasn’t done in actual reality,” she said. “Now we have the opportunity to set the standard there.”

Read More: builtin.com

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  XRP

XRP  Tether

Tether  Solana

Solana  Dogecoin

Dogecoin  USDC

USDC  Cardano

Cardano  Lido Staked Ether

Lido Staked Ether  TRON

TRON  Chainlink

Chainlink  Avalanche

Avalanche  Wrapped stETH

Wrapped stETH  Sui

Sui  Wrapped Bitcoin

Wrapped Bitcoin  Toncoin

Toncoin  Stellar

Stellar  Hedera

Hedera  Shiba Inu

Shiba Inu  Polkadot

Polkadot  WETH

WETH  LEO Token

LEO Token  Litecoin

Litecoin  Bitcoin Cash

Bitcoin Cash  Bitget Token

Bitget Token  Hyperliquid

Hyperliquid  Uniswap

Uniswap  Official Trump

Official Trump  USDS

USDS  Wrapped eETH

Wrapped eETH  Pepe

Pepe  NEAR Protocol

NEAR Protocol  Ethena USDe

Ethena USDe  Aave

Aave  Aptos

Aptos  Internet Computer

Internet Computer  Monero

Monero  WhiteBIT Coin

WhiteBIT Coin  Ondo

Ondo  Ethereum Classic

Ethereum Classic  Cronos

Cronos  POL (ex-MATIC)

POL (ex-MATIC)  Mantle

Mantle  Render

Render  Dai

Dai  MANTRA

MANTRA  Algorand

Algorand