Introduction

The metaverse is a word composed of “meta” (μετά, the Greek preposition for “after”) and “verse” out of “universe.” In the virtual world of metaverse, people can interact, work, enjoy leisure activities and go shopping with their friends, family and even strangers through technologies such as VR (Virtual Reality) and AR (Augmented Reality). With the rise of the metaverse, our lifestyle is expected to change to a certain extent. “Design,” according to Article 121, Paragraph 1 of the Taiwan Patent Act, means the creation made in respect to the shape, pattern, color, or any combination thereof, of an article as a whole or in part by visual appeal. Likewise in Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the China Patent Law, “Design” means a new design of the shape, pattern, or a combination thereof, as well as a combination of the color, shape and pattern, of the entirety or a portion of a product, which creates an aesthetic feeling and is fit for industrial application. Since virtual articles or products in the metaverse are just like their equivalents in real life, this article therefore intends to preliminarily explore how or whether it is possible to obtain design patent protection for the appearances of articles or products in the metaverse.

I. What Is The Metaverse?

In 1992, the term “metaverse” featured in a science fiction novel, Snow Crash, for the first time. In this novel, author Neal Stephenson conceptualized the metaverse as a completely virtual world, a 3D virtual space analogous to the real world where people could live, explore and interact with one another as avatars. People can do anything in the metaverse that you can do in the real world, and even they can do a lot of things which cannot be achieved in the real world, like instant movement. We were able to have a glimpse of the metaverse through the fine images of the OASIS presented in the movie “Ready Player One” [1].

From a business perspective, Facebook announced on October 28, 2021 that it would officially change its name to “Meta” to develop social media in the virtual world. At the same time, Microsoft also officially announced its full-scale entry into the metaverse and the incorporation of its MR (Mixed Reality) meeting platform, Microsoft Mesh, into Microsoft Teams to create a virtual world of an office environment. According to Bloomberg, the metaverse market could reach US$800 billion by 2024 if the current trend of metaverse continues, while a new study by McKinsey & Company also indicates that the value of the metaverse could grow to US$5 trillion by 2030 [1], all of which suggests considerable business opportunities are calling.

In terms of technology, as mentioned earlier in the introduction, the metaverse is produced through technologies such as VR and AR. To be more specific, its core technologies include AI (Artificial intelligence), VR, AR, MR and blockchain, each of which can be divided into (1) hardware such as semiconductor and information devices, and (2) software for building virtual worlds.

II. Metaverse Design Patents

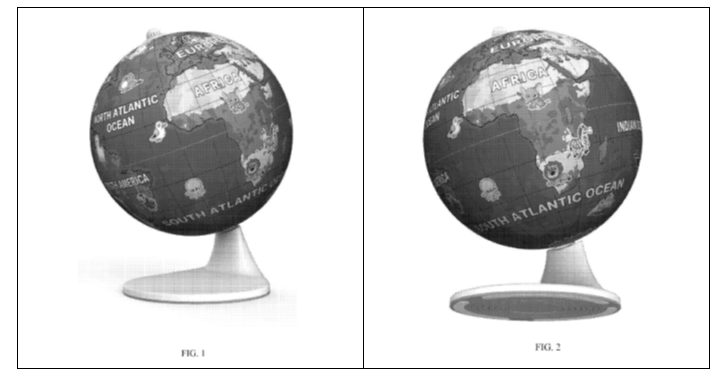

In the metaverse, manufacturers may not only use trademarks to distinguish the origin of their virtual products or services from those of others, but also the designs of the appearances of their products to attract consumers in the metaverse to buy their virtual products. Therefore, there certainly also exists intellectual property issues concerning trademarks, designs, copyrights and the like in the metaverse. In fact, a number of world-famous companies, including McDonald’s, Victoria’s Secret, L’Oréal Paris, BYD Company and Nike, have already started to develop trademark portfolios in the metaverse by filing applications with major patent and trademark offices. There are growing numbers of applicants who have filed applications for metaverse design patents with, for instance, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). For example, U.S. Design Patent No. USD893,616S (perspective views 1 and 2 reproduced below) designates an article to which a design is applied via its design title, “Augmented Reality Globe.” As for the manner in which the drawings are presented, there are no difference from the way that other design patents of ordinary articles are presented with perspective views (as shown below), that is., a perspective view, six-sided views and the like. In the practice of design patents in the United States, the title of a design can be used to determine the article to which the design is applied, hence the title of a patent is of utmost importance. To take the example of the Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc. case [2], Curver sued Home Expressions for selling baskets which infringed its U.S. design patent no. D677,946, but the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) held that the title of U.S. design patent no. D677,946, “Pattern for a Chair,” is a drawing of “chair” whose claim does not cover a “basket.” Therefore, said baskets did not constitute an infringement.

Perspective views 1 and 2 of USD893,616S

Furthermore, taking the drawings of U.S. Design Patent No. USD947,874S as another example, the non-claimed part of the design is represented with broken lines (as shown below in Fig. 7, reproduced on the left), while the emphasis is on the “virtual space” presented in the VR glasses (as shown below in Fig. 8, reproduced on the right).

Figures 7 and 8 of USD947,874S

To our knowledge, the above is the current filing practice of metaverse design patents in the United States, and subsequent development requires further observations. In the following section, we explore issues related to metaverse design patents both in Taiwan and China:

I. In Taiwan

Regarding the design of a tangible device (e.g., VR glasses) for accessing the metaverse, it has no difference from the common designs of other tangible products with three-dimensional shapes, and thus certainly they are patentable subject matter for a design patent, and the required filing documents are the same as those for the common designs. In addition, according to the TIPO article “Relationship between Metaverse and Design Patents” published on June 13, 2022, design cases of products with three-dimensional shapes are not classified as metaverse design patent cases. Instead, the TIPO classifies metaverse design patent cases into three categories according to their properties, namely “virtual space,” “virtual articles” and “human-machine interface.”

A. Virtual Space (such as the non-physical space seen through VR glasses): The preparation of the drawings for this category of design patent case can be presented in a manner similar to the presentation of design patent drawings for “interior designs” in the Patent Examination Guidelines.

B. Virtual Article (such as game treasures and non-fungible tokens (NFTs)): The preparation of the drawings for this category of design patent case can be presented in a manner similar to the presentation of design patent drawings for “common articles” in the Patent Examination Guidelines.

C. Human-Machine Interface (such as operating interface): The preparation of the drawings for this category of design patent case can be presented in a manner similar to the presentation of design patent drawings for “graphic user interface (GUI)” in the Patent Examination Guidelines.

It should be noted that the above three categories of meta-universe design patent cases should be identified as “computer program products” in the specification so as to be distinguishable from physical product design patent cases. This is because that the TIPO recognizes that non-physical product designs are digital designs generated by software, and that “computer program products” are the source of such digital designs, and thus they defined these products to which such digital designs are applied as “computer program products” in 2020 by amending its Patent Examination Guidelines.

II. In China

A. With regard to the design of a product with a specific shape, such as the design of a hardware device to access the metaverse (e.g., VR glasses), the design patent practice in China is similar to that in Taiwan. Applicants can obtain protection of a design patent in China by applying for a common design patent.

B. According to Ordinance No. 68 promulgated by the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) on March 12, 2014, China has opened up the protection of GUI design patents since May 1, 2014, but not all software interface of an electronic product is allowed to be granted a design patent. According to design patent practice in China, a GUI is patentable, if the GUI:

(1)is incorporated in a specific hardware product; given this, an interface design independent from the hardware is not patentable; and

(2)is able to conduct human-machine interaction.

Accordingly, graphics displayed by a game interface and that by display devices unrelated to human-machine interaction, such as electronic screen wallpapers, boot/shutdown screens, and graphic layout of webpages irrelevant to human-machine interaction, cannot be granted design patents. Based on the above criteria, further analysis is required on a case-by-case basis with regard to whether the GUI of various operating software innovated in the field of metaverse can be granted a design patent.

C. In addition, it is still under discussion in China whether the designs of various “products” created in the virtual world of the metaverse can be subject matter of design patents. As mentioned above, the metaverse is a virtual world in which people can work and live, and hence there will certainly be various virtual articles or products similar to actual products in the real world, such as villas, cars, desks, sofas and table lamps. Analyses are required based on the definition of design products in the China Patent Law with regard to whether the appearances of such virtual product designs can be protected by the Patent Law. According to the provisions of Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the China Patent Law, as stated earlier, “Design” means a new design of the shape, pattern, or a combination thereof, as well as a combination of the color, shape and pattern, of the entirety or a portion of a “product,” which creates an aesthetic feeling and is fit for industrial application. Consequently, the first thing to consider is whether the “products” in the virtual world of the metaverse belong to the design products defined by the China Patent Law. In the authors’ opinion, according to current China patent practice, virtual products in the metaverse do not seem to be considered a design product as defined by the China Patent Law. This is because neither are these virtual products a kind of industrial product after all, nor are they designs suitable for industrial applications even if they can bring users good experiences in the metaverse. Moreover, according to China’s “Patent Examination Guidelines,” only designs that can be applied to industry and that can be mass produced meet the qualifications of “industrial application” under the China Patent Law. Product designs in the metaverse, on the other hand, are not considered to be able to achieve mass production in the conventional sense.

III. Conclusion

Currently, the number of applications and/or approvals of metaverse design patents in Taiwan and abroad is still small, indicating that each country is still at an early stage of exploration. From the above-mentioned article referred by the TIPO, one may conclude that Taiwan holds an open attitude towards metaverse design patent application cases and has also provided relevant application guidelines. As for China, it may take a longer time for the CNIPA to deal with the issue of metaverse design patents. Nevertheless, one thing for certain is that the metaverse will continue to develop. Meanwhile, major international companies such as Meta, Microsoft and NVIDIA have recently formed the “Metaverse Standards Forum,” aiming to standardize the metaverse industry. It is believed that countries or regions will gradually open up or further relax the conditions for metaverse design patent applications in response to this trend in the foreseeable future.

Read More: news.google.com

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  Tether

Tether  XRP

XRP  Solana

Solana  Dogecoin

Dogecoin  USDC

USDC  Cardano

Cardano  Lido Staked Ether

Lido Staked Ether  TRON

TRON  Avalanche

Avalanche  Sui

Sui  Wrapped stETH

Wrapped stETH  Toncoin

Toncoin  Chainlink

Chainlink  Shiba Inu

Shiba Inu  Wrapped Bitcoin

Wrapped Bitcoin  Stellar

Stellar  Hedera

Hedera  Polkadot

Polkadot  WETH

WETH  Bitcoin Cash

Bitcoin Cash  LEO Token

LEO Token  Uniswap

Uniswap  Litecoin

Litecoin  Hyperliquid

Hyperliquid  Pepe

Pepe  Wrapped eETH

Wrapped eETH  NEAR Protocol

NEAR Protocol  Ethena USDe

Ethena USDe  USDS

USDS  Internet Computer

Internet Computer  Aptos

Aptos  Aave

Aave  Mantle

Mantle  Cronos

Cronos  Render

Render  POL (ex-MATIC)

POL (ex-MATIC)  MANTRA

MANTRA  Ethereum Classic

Ethereum Classic  Bittensor

Bittensor  WhiteBIT Coin

WhiteBIT Coin  Monero

Monero  Virtuals Protocol

Virtuals Protocol  Artificial Superintelligence Alliance

Artificial Superintelligence Alliance  Dai

Dai  Tokenize Xchange

Tokenize Xchange