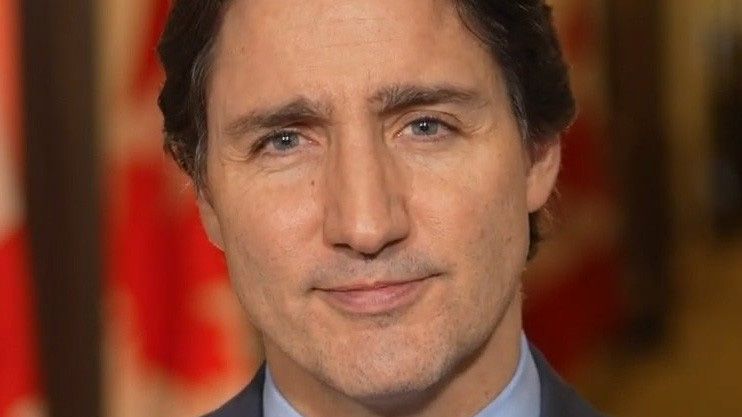

Los Angeles Unified is the latest target of ransomware attacks among school districts in California.

Mikhail Zinshteyn/EdSource

Mikhail Zinshteyn/EdSource Los Angeles Unified is the latest target of ransomware attacks among school districts in California.

As ransomware attacks continue to target education systems, school districts across California and the nation are trying to figure out how to best reduce the risk and protect their data and information technology.

“It’s not a question of if a school system will experience a cybersecurity incident. It’s only a matter of when,” said cybersecurity expert Doug Levin, the national director of nonprofit K12 Security Information Exchange. “Those risks need to be part of the ongoing governance and operations of school districts.”

Districts have turned to cyber insurance, set up backup systems and installed extra security measures such as requiring double authentication to gain access to data. And firsthand experience has pushed many to reevaluate the data they keep. Meanwhile, both state and federal governments are beginning to take steps to more closely monitor attacks.

“We’re just trying to double down now and do whatever we can to ensure that, if it does happen again, that we can make it as small and less impactful as possible,” said Ryan Pinkerton, the superintendent of business at San Luis Coastal Unified, which suffered a ransomware attack in May.

A prominent recent example was at Los Angeles Unified, which was targeted over Labor Day weekend. The crime syndicate that attacked the district posted some of its data online after the district chose not to negotiate or pay a ransom, following advice from law enforcement.

While LAUSD did not pay a ransom, some experts speculate that payments may have been made by other districts. Districts do not always disclose such information, according to Levin. The sensitivity of the hacked information as well as the time and resources it would take to recover lost data all play a part in that decision, he added.

So far this year, ransomware attacks have hit more than 60 school districts, colleges and universities across the country, according to data from cybersecurity firm Emsisoft, which tracks known incidents. That includes at least 30 K-12 public school systems, but the situation may be much worse because districts are not required to report such incidents, Emsisoft threat analyst Brett Callow said.

Though the education sector is expected to close out the 2022 year with a lower number of attacks than the last two years — which had more than 80 incidents each — this year’s ransomware attacks continue to reflect a significant interest by hackers in the school sector.

“I do think that there’s a need for more and better information sharing in the K-12 community,” Levin said. “I think these incidents need to be understood as being much more commonplace. It’s something that school districts need to actively manage and plan for.”

Part of that problem is that districts tend to have small information technology teams relative to the size of their operations, and their computer systems tend to be older and out of date, Levin said.

In California, there have been three incidents so far this year, including one that affected multiple districts under the Glenn County Office of Education in the Sacramento Valley. There, with computer systems down, schools and administrative offices were forced to return to pen and paper to teach and perform administrative tasks. The May attack, which affected 75% of the education office’s districts, stole and then encrypted student records, financial and payroll data and impacted the district’s ability to process checks.

School days never had to be canceled, but it’s been a slow recovery since then, Superintendent Tracey Quarne said. The district had to create a second email system and a new financial system as a result. It’s been a frustrating experience, he said.

“Talk to the smartest IT person you can find,” he said, referencing the steps he hopes other districts will take. “Trust them. Do exactly what they say. And do not trust your federal or state government to protect you.”

Quarne wouldn’t comment on whether the Glenn County Office of Education paid a ransom or whether any of its data had been published since the breach, saying the incident was still under investigation.

Districts sometimes quietly decide to pay ransoms after evaluating the sensitivity of the hacked information, and the time and resources it would take to recover lost data also play a part in that decision, expert Levin said.

Neither LAUSD nor San Luis Coastal Unified, which were the targets of the other two known incidents this year, paid a ransom, but both had data posted to the dark web, putting individuals and vendors at risk for exploitation. Both were targeted over three-day weekends and had the same crime syndicate claim responsibility for the attacks.

Crime syndicate Vice Society, which appears to operate from Russia, has claimed credit for 10 different attacks on the U.S. education sector this year, causing the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency to put out an alert in September warning of its disproportionate attacks on schools.

At Los Angeles Unified, the impact was not as bad as expected. The ransomware attack was discovered as it was happening, so the district was able to stop it before it could spread. As a result, the crime syndicate was only able to pull 500 gigabytes of the 16 million gigabytes of data stored across the district, according to Superintendent Alberto Carvalho.

Though the amount was small in comparison with the amount of data the district keeps, analyst Callow said that the severity of a hack depends more on what data was taken.

The Los Angeles district confirmed that information from some private vendors as well as some data such as names, addresses, student identification numbers and academic information from students who attended LAUSD schools between 2013 and 2016 were posted to the dark web after the district refused to negotiate with the crime syndicate. The district is still working to let individuals who have been affected know as it sifts through the data.

The district did not have to cancel school after the attack, but some operations were disrupted.

At San Luis Coastal Unified, events unfolded slightly differently. The district was attacked Memorial Day weekend but was able to quickly switch to a backup system. Though the district did not engage with Vice Society, data wasn’t uploaded to the dark web until months later, according to IT director Jeremy Koellish. Hackers put online information from around 4,000 vendors and employees who worked at the district between 2012 and this year, according to Assistant Superintendent of Business Services Ryan Pinkerton.

“We had had a backup system; we had been monitoring. We felt like we were on it,” Pinkerton said about the status of its cybersecurity prior to the attack.

San Luis Coastal Unified is now sifting through its archive, reconsidering which records are necessary to keep and which are best to remove from its servers to minimize the impact of any future data breaches.

“It’s really made the district go through and look at, what are we saving? And why are we saving it?” Pinkerton said.

The district also now has software in place to monitor its servers daily and is working toward implementing two-factor authentication, which threat analyst Callow said is one of the most important steps a district can take to ensure its security.

LAUSD was in the process of implementing multifactor authentication when the attack happened in September.

According to Callow, it’s getting more difficult to qualify for and afford cyber insurance without basic steps like multifactor authentication in place. And the insurance, he said, can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it pushes organizations to improve their security, but on the other, it may mean an organization is more likely to pay ransom demands.

As LAUSD looks to increase its cybersecurity in the wake of the attack, the school board has given Carvalho broad emergency power to address it. The district has also convened a task force of cybersecurity experts to recommend additional measures, which it will outline in a report in December.

It is not clear yet how much LAUSD will spend on reducing the threat. Public school systems such as Baltimore County Public Schools in Maryland, which serves less than a quarter of the number of students LAUSD does, paid $8.1 million in recovery costs after an attack in 2020.

Education organizations and school districts like LAUSD have been pushing for the Federal Communications Commission to allow E-rate funding, meant to make digital information services more affordable for schools and libraries, to be used toward cybersecurity.

California is also taking notice. Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill in September requiring K-12 schools to report cyberattacks and other security breaches to the state. The California Cybersecurity Integration Center will create a registry of reported cyberattacks. However, reporting will only be mandated for incidents that affect more than 500 individuals.

On the federal level, Congress passed the K-12 Cybersecurity Act last year requiring the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency to conduct a study — still ongoing — about cybersecurity risks affecting K-12 schools. The U.S. Government Accountability Office recommended that the Department of Education update its guidelines on cybersecurity, which have not been changed since 2010. However, these efforts have yet to bring tangible results, according to expert Levin.

For now, the most important thing a district can do is actively prepare for the possibility of a ransomware attack and be sure that it understands the risks, Levin said.

“I think these incidents need to be understood as being much more commonplace,” he said. “Something that school districts need to actively manage and plan for, budget against and even sort of practice their plans for.”

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Read More: edsource.org

Vana

Vana  PAX Gold

PAX Gold  Polygon PoS Bridged WETH (Polygon POS)

Polygon PoS Bridged WETH (Polygon POS)  Dash

Dash  Trust Wallet

Trust Wallet  Creditcoin

Creditcoin  Ether.fi

Ether.fi  Goatseus Maximus

Goatseus Maximus  Astar

Astar  PayPal USD

PayPal USD  Telcoin

Telcoin  TrueUSD

TrueUSD  GRIFFAIN

GRIFFAIN  Theta Fuel

Theta Fuel  io.net

io.net  Stader ETHx

Stader ETHx  Usual

Usual  AgentFun.AI

AgentFun.AI  Swell Ethereum

Swell Ethereum  BOOK OF MEME

BOOK OF MEME  CHEX Token

CHEX Token  Zerebro

Zerebro  Swarms

Swarms  Zilliqa

Zilliqa  Moca Network

Moca Network  WOO

WOO  Holo

Holo  tBTC

tBTC  Super OETH

Super OETH  0x Protocol

0x Protocol  Horizen

Horizen  JUST

JUST  Ondo US Dollar Yield

Ondo US Dollar Yield  Neiro

Neiro  Enjin Coin

Enjin Coin  GMT

GMT  Magic Eden

Magic Eden  Aethir

Aethir  Golem

Golem  Bridged USDC (Polygon PoS Bridge)

Bridged USDC (Polygon PoS Bridge)  AI Rig Complex

AI Rig Complex  Convex Finance

Convex Finance  QuantixAI

QuantixAI  DeepBook

DeepBook  Celo

Celo  Basic Attention

Basic Attention  Verus

Verus  Memecoin

Memecoin  Ankr Network

Ankr Network