To print this article, all you need is to be registered or login on Mondaq.com.

In Short

The Situation:Under the existing legal regimes,

decentralized autonomous organizations (“DAO” or

“DAOs”) have been viewed as a way to hedge against

regulatory action by way of a decentralized structure. The

Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s (“CFTC”)

recent and first attempt to impose liability on a DAO and its

members disrupts that assumption and helps provide insight into the

future of decentralized finance (“DeFi”) in the United

States.

The Result: The CFTC’s recent Order found bZeroX, LLC and its two founders

violated the Commodity Exchange Act (“CEA”) by unlawfully

engaging in activities that could lawfully be performed only by a

registered futures commission merchant (“FCM”) or

designated contract market (“DCM”), and contended that

individual DAO members that voted on governance measures are

jointly and severally liable for debts of the DAO as an

unincorporated association.

Looking Ahead: The CFTC’s complaint against

Ooki DAO (the successor to bZeroX’s DAO that operated the same

software protocol as bZeroX) charged the same violations that the

CFTC found in the Order. Even if the federal court does not adopt

the CFTC’s “unincorporated association” theory of

liability for DAO voters, its very prospect seems likely to chill

DeFi participation in the United States in the near future.

On September 22, 2022, the CFTC filed an Order announcing it had

reached a settlement with bZeroX, LLC and its two founders, Kyle

Kistner and Tom Bean (collectively, “Respondents”). The

settlement relied in part on imposing controlling person liability

on the founders, under Section 13(b) of the CEA, for bZeroX’s

violations of CEA Sections 4(a) and 4(d)(1). The Order found that

the Respondents violated the CEA by operating an Ethereum-based

DeFi platform (“bZx Protocol”) that accepted orders and

facilitated tokenized leveraged retail trading of virtual

currencies such as ETH, DAI, and others.

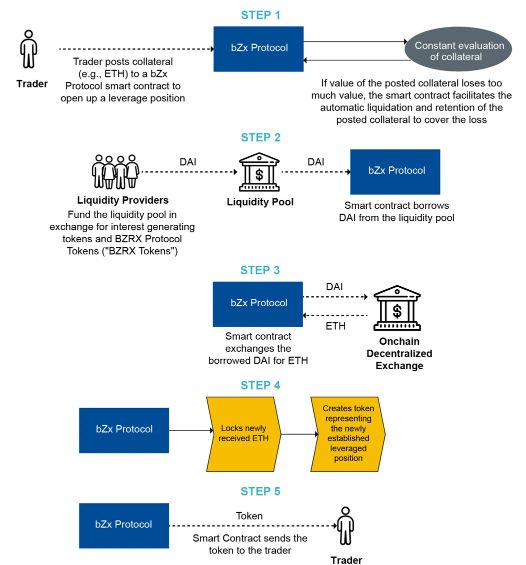

According to the Order, the bZx Protocol permitted users to

contribute margin to open leveraged positions, the ultimate value

of which was determined by the price difference between two digital

assets from the time the position was established to the time it

was closed. In doing so, the CFTC found, the Respondents

“unlawfully engaged in activities that could only lawfully be

performed by a designated contract market (“DCM”) and

other activities that could only lawfully be performed by a

registered futures commission merchant (“FCM”).” The

CFTC also found, by Respondents failing to conduct

know-your-customer diligence on customers as part of a customer

identification program, as required of both registered and

unregistered FCMs, that the Respondents violated CFTC Regulation

42.2. Below is an illustration of how the bZx Protocol

operated.

Concurrently with the Order, the CFTC filed a complaint against Ooki DAO, the successor to

the bZx DAO-a DAO comprising bZx Protocol token holders that

Respondents had transferred control to following a series of hacks

in 2020 and early 2021. The Ooki DAO complaint charges the same

violations in which the CFTC found in the Order that the

Respondents had engaged. The CFTC characterized Ooki DAO in the

Order as “an unincorporated association comprised of holders

of Ooki DAO Tokens who vote those tokens to govern (e.g. to modify,

operate, market, and take other actions with respect to) the [Ooki]

Protocol.” In the Order, the CFTC stated that

“[i]ndividual members of an unincorporated association

organized for profit are personally liable for the debts of the

association under principles of partnership law.”

As discussed in Commissioner Mersinger’s dissent

(“Mersinger’s Dissent”), neither the CEA nor the CFTC

have ever defined a DAO. More importantly, although the CFTC has to

date settled one action against what it characterized as a DeFi

trading platform (Blockratize, Inc. d/b/a Polymarkets.com), the

Ooki DAO complaint is the first time it has attempted to impose

liability on a DAO or its members. This was not entirely

unexpected. For example, in footnote 63 in the CFTC’s Digital Asset Actual Delivery

Interpretive Guidance, the CFTC noted that “in the context

of a ‘decentralized’ network or protocol, the Commission

would apply this interpretation to any tokens on the

protocol that are meant to serve as virtual currency as described

herein” (emphasis added).

The CFTC added that “[i]n such instances, the Commission

could, depending on the facts and circumstances, view

‘offerors’ as any persons presenting, soliciting, or

otherwise facilitating ‘retail commodity transactions,’

including by way of a participation interest in a foundation,

consensus, or other collective that controls operational decisions

on the protocol, or any other persons with an ability to assert

control over the protocol that offers “retail commodity

transactions,” as set forth in CEA section

2(c)(2)(D).”

Former CFTC Commissioner Berkovitz also stated in a 2021 speech that “[n]ot only

do I think that unlicensed DeFi markets for derivative instruments

are a bad idea, I also do not see how they are legal under the

CEA.” A few years prior to that, a CFTC spokesperson stated in response to

questions about Augur-a DeFi prediction market offering, among

other things, assassination contracts-that “[w]hile I

won’t comment on the business model of any specific company, I

can say generally that offering or facilitating a product or

activity by way of releasing code onto a blockchain does

not absolve any entity or individual from complying with pertinent

laws or CFTC regulations[.]” The CFTC’s unincorporated

association theory of liability is not unique: The SEC’s 2017 DAO Report pointed out that

Section 3(a)(1) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 defines an

“exchange” as “any . association, or group of

persons, whether incorporated or unincorporated..”

However, as noted in Mersinger’s Dissent, “[d]efining

the Ooki DAO unincorporated association as those who have voted

their tokens inherently creates inequitable distinctions between

token holders.” For instance, a single vote on a generic

governance proposal having nothing to do with the CEA or CFTC rules

could unknowingly subject token holder A to membership in the

unincorporated association, as defined by the CFTC, and assumption

of personal liability, while token holder B escapes

membership/liability by virtue of incidentally neglecting to vote.

Even if token holder A had voted directly against the alleged

unlawful actions, it could still face joint and several liability

for the full legal claim against the DAO.

Moreover, as noted in Mersinger’s Dissent, the CEA

“sets out three legal theories that the Commission can rely

upon to support charging a person for violations of the CEA or CFTC

rules committed by another: (i) principal-agent liability; (ii)

aiding-and-abetting liability; and (iii) control person

liability.” The CFTC has pursued the aiding-and-abetting

theory in somewhat similar circumstances. In January 2018, the CFTC charged Jitesh Thakkarand Edge Financial

Technologies, Inc.-a company Mr. Thakkar founded and for which

he served as president-with aiding and abetting Navinder Sarao in

engaging in a manipulative and deceptive scheme by designing

software used by Mr. Sarao to spoof mini S&P futures

contracts.

Mr. Thakkar was also named in a criminal complaint brought by

the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) related to the same

conduct on charges of conspiracy to commit spoofing as well as

aiding and abetting spoofing. The CFTC agreed to stay its case

during the pendency of the criminal matter. After the DOJ’s

charges were dismissed with prejudice in April 2019, the

CFTC resumed its civil action against Mr. Thakkar in September

2019. One year later, the CFTC ultimately entered into a consent order for permanent injunction with

Mr. Thakkar’s company, Edge Financial Technologies, Inc. The

order included findings tracking the allegations in the CFTC’s

complaint, a permanent injunction against aiding-and-abetting

violations of CEA Sections 4c(a)(5)(C) (spoofing) and 6(c)(1)

(manipulation) and CFTC Regulation 180.1(a)(1) and (3) (relating to

the use of a manipulative and deceptive device, scheme, or artifice

to defraud), and an order of disgorgement and civil monetary

penalty totaling $72,600.

While Commissioner Mersinger may have wished to hold only the

founders liable for DAO-related activity, it would seem that the

Commission is not so inclined and may wish to send a message to

those who would trade on unlawful venues, even though the

Commission usually seeks to protect such persons against misconduct

arising from trading on such venues. In the case of DAOs, the

Commission may take the view that such persons operate and control

the venues, in some ways.

Even if this “unincorporated association” theory of

DAO liability is not ultimately endorsed by a federal court, this

ruling will likely result in protocol founders increasingly

choosing to maintain anonymity and/or operate offshore. This could

result in decreased availability of DeFi derivatives trading to

U.S. persons and, if DeFi derivatives trading remains available to

U.S. persons from offshore, greater extraterritorial enforcement

efforts by the CFTC.

More broadly, this action is a warning that some regulators view

unregulated DeFi trading activity as incompatible with existing

legal structures, notwithstanding the argument that DAO token

holders are engaged in active management of the protocol and so are

not dependent on the efforts of others under SEC v. Howey

Co. Footnote 10 of the bZeroX Order sounds loud and clear on

this point, warning that “[i]t was (and remains)

Respondents’ responsibility to avoid unlawfully engaging in

activities that could only be performed by registered entities and,

should they ever wish to register, to structure their business

in a manner that is consistent with Commission registration

requirements” (emphasis added).

Incidentally, the message in that footnote is the answer to questions raised by some as to how crypto

businesses are to operate when their very structures seem

incompatible with existing regulatory schemes. More recently, SEC Chairman Gensler expressed a

similar sentiment, stating that “[t]he commingling of the

various functions within crypto intermediaries creates inherent

conflicts of interest and risks for investors. Thus, I’ve asked

staff to work with intermediaries to ensure they register each of

their functions- exchange, broker-dealer, custodial functions, and

the like-which could result in disaggregating their functions

into separate legal entities to mitigate conflicts of interest and

enhance investor protection” (emphasis added).

DAOs possess many novel qualities not present in traditional

corporate structures-transitory ownership tied to a tradeable

token, user ownership and governance, and operations conducted by,

in some cases, an autonomous smart contract code. While

encompassing only active voters in the instant case, the CFTC’s

language in its complaint against Ooki DAO seems to suggest that a

smart contract protocol running programs deemed to violate

regulations could continuously generate liability for DAO members

simply by way of the members having “permitted”

transactions executed by such programs. The greater the autonomy

and automation of the smart contract underlying the protocol, the

less sense attaching joint and several liability to DAO members

arguably makes. Automating protocol functions to reduce the

necessity of DAO member input is another foreseeable result of the

CFTC’s position.

While the potential for DAOs to avoid classification of their

tokens as securities has reinforced the use of a fully

decentralized structure lacking legal form, the countervailing risk

of a general partnership-and especially voting member liability as

an “unincorporated association”-will likely lead to

increased use of traditional legal

entities in DAO formation and governance for the DAO and

individual participants alike. For all of the innovation the unique

traits of a DAO allows, it is becoming increasingly clear that

existing regulations will demand the rails of legal personhood to

achieve compliance.

Whether a “test case” ramping up to something larger

or simply a reminder to founders-or those who otherwise seek to

legally or practically distance themselves from the DAOs that they

create (e.g., by the developers “giv[i]n[g] up ownership over the ‘escape

hatch’ function, which would allow a designated party to shut

the system down[]”)-that DAOs cannot be used as a tool to

evade regulatory action, the outcome of the CFTC’s lawsuit

against Ooki DAO is one to closely watch as a harbinger for DeFi as

a whole. User ownership and voted token participation in DAOs-while

not the regulatory shield some might wish it to be-is an idea

unlikely to go away anytime soon.

Three Key Takeaways

- The CFTC’s Ooki DAO complaint serves as warning to the DeFi

market to conform to the existing legal structure and could place a

premium on founder anonymity or reduce DeFi protocol access for

U.S. citizens. This outcome could result in further

extraterritorial enforcement efforts by the CFTC as protocols shift

operations overseas to avoid unlawfully engaging in activities

allowable only by registered entities. - The CFTC finding active voters personally liable under

principles of partnership law will likely cause DAOs to increase

their levels of autonomy and automation, which would reduce the

necessity of DAO member input and make the argument attaching joint

and several liability to DAO members less viable. - The risk of DAOs’ classification as general partnerships

and individual voting members’ potential personal liability

under an unincorporated association theory will likely lead to the

increased use of traditional legal entities in DAO formation and

governance.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.

Read More: www.mondaq.com

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  Tether

Tether  XRP

XRP  Solana

Solana  USDC

USDC  Cardano

Cardano  Dogecoin

Dogecoin  TRON

TRON  Lido Staked Ether

Lido Staked Ether  Wrapped Bitcoin

Wrapped Bitcoin  Pi Network

Pi Network  LEO Token

LEO Token  Chainlink

Chainlink  Toncoin

Toncoin  Stellar

Stellar  USDS

USDS  Wrapped stETH

Wrapped stETH  Hedera

Hedera  Avalanche

Avalanche  Shiba Inu

Shiba Inu  Sui

Sui  Litecoin

Litecoin  MANTRA

MANTRA  Bitcoin Cash

Bitcoin Cash  Polkadot

Polkadot  Ethena USDe

Ethena USDe  Bitget Token

Bitget Token  WETH

WETH  Binance Bridged USDT (BNB Smart Chain)

Binance Bridged USDT (BNB Smart Chain)  Hyperliquid

Hyperliquid  WhiteBIT Coin

WhiteBIT Coin  Wrapped eETH

Wrapped eETH  Monero

Monero  Uniswap

Uniswap  sUSDS

sUSDS  Aptos

Aptos  Dai

Dai  NEAR Protocol

NEAR Protocol  Pepe

Pepe  OKB

OKB  Internet Computer

Internet Computer  Mantle

Mantle  Ondo

Ondo  Gate

Gate  Ethereum Classic

Ethereum Classic  Tokenize Xchange

Tokenize Xchange  Aave

Aave  Coinbase Wrapped BTC

Coinbase Wrapped BTC